Anyone who’s spent a substantial amount of time and energy on poker knows what variance is, and is familiar with the type of discussion the topic tends to elicit, as well as the variety of emotions these discussions can elicit. Everything from celebrating a big score to commiserating over a huge downswing boils down to a discussion about variance, and these discussions, in large part, help to frame our understanding of many key poker concepts.

The way we talk about variance as poker players can often leave a lot to be desired – it could be argued that we should talk about it a lot less, since we end up complaining about it so often when we do – but there’s no doubt that talking about it is necessary to some extent. Coming to terms with what variance truly is, and how it works, is a central part of our poker development.

But in doing so, we often develop unhealthy or damaging ideas about the concept. We often grow so attached to the idea of reducing variance that we forget how necessary variance is in the first place – we become poker players who wish they were chess players. Let’s take a look at how we might see long-term benefits from applying more specific terminology when talking about variance, and shifting our own personal perceptions about the term itself.

Common misconceptions about variance

The single most common misconception about variance in poker is that we have control over when we ‘accept’ or ‘decline’ variance, and thus, that we have control over how much variance we experience. The perception exists that different types of players in different games are subjected to variance to different degrees, dependent upon the choices they make.

For example, loose-aggressive tournament players are often described as playing a “high-variance” style, simply because their stack usually ends up fluctuating upwards or downwards on a frequent basis. However, this perspective ignores one of the fundamental realities of variance – it’s happening before you even realize it’s happening, whether you like it or not.

Imagine you fold a particular spot in an MTT where you had the chance to take a coinflip for your tournament life, because you wanted to lower your variance. In the leadup to that situation, you’ve already been subjected to a great deal of variance – there was variance in your decision to register the tournament (maybe some days you don’t feel like playing it). There was variance in the fact that you made it to this point (you won some hands, lost some hands). There was variance in the fact that your opponent made the decision that they did (maybe with some frequency they would have simply folded, or made a different decision that changed the action as it came to you). Above all, there was variance in the fact you got dealt the cards that led to you facing a close decision at this point – sometimes you just get dealt 72o and fold.

So with all that variance in play, can we even say with any confidence that it’s possible to avoid variance? Of course not. It’s part of the game. Instead, what we actually mean in many cases when we talk about variance, is volatility. When we fold in a spot we could have called, we’re sometimes trying to avoid playing a big pot with uncertain results in favor of a small one with certainty – this is reduction of volatility, and it’s something we do control to some extent.

The many forms of volatility

The many forms of volatility

Volatility exists in many ways. It exists in the game selection decisions we make, and our bankroll management choices – the more aggressive our game selection and bankroll management choices, the more volatility we experience. It exists in the decisions we make at the table – players who are seeking to reduce volatility for whatever reason (maybe they believe they have a huge edge in the tournament) are likely to take more passive lines, or avoid playing large pots. The bigger the size of the average pot you play, the more volatile your results will be.

It also exists in our decisions themselves. From time to time we’ll find ourselves in a very unique spot at the table, a real one-off hand where something particularly unusual or crazy happens. These are volatile spots – they come around rarely, and one decision in a big pot can have a huge influence on what happens afterwards.

Take Jonathan Duhamel’s decision to make a somewhat questionable call-off on the turn versus Matt Affleck in the 2010 Main Event – Duhamel calls, hits his 10-outer and goes on to win the tournament. If he folds there and reduces his volatility, he preserves his stack and makes a most likely better play in the long run, but do his chances of winning the Main Event go up or down? The question has no clear answer.

Value vs growth

The reason why this question has no clear answer is because we can’t possibly know what would have happened if Duhamel had folded, or if he called and lost. Maybe Affleck wins the Main Event that year. But regardless, it’s an interesting example of a situation where a short-term negative went on to become a long-term positive for Duhamel – the play he made had a negative expected value on the turn, most likely, but he’s gained a lot of fame and endorsement money from winning the main event.

Back in the November Nine era, it could have been argued that the endorsement money going along with winning the Main Event might have been big enough that it justified making some very marginal decisions in the run-up to the final table, simply to have a shot at that money – if we could extrapolate what would happen to each player’s life and career in the X% of instances that they won the Main Event, we might find out that for some of them, the benefits of a greater shot at winning might actually outweigh the losses that come with bubbling the final table, for example.

Obviously this is an extreme situation, but we must bear it in mind with our own choices. Sometimes shot-taking at a really good tournament outside of our usual buyin range might be worth it, since it allows for exponential growth in our bankroll if we do win or cash big, and potentially for some players the ability to quit their job or turn professional.

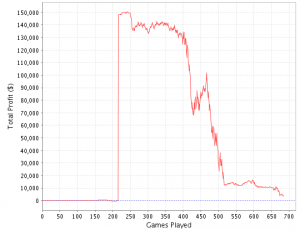

On the other hand, a strategy that relies upon consistent growth of our bankroll and available resources means we can plan ahead much more effectively, and make much more accurate assumptions about the kind of bankroll we might have further down the line – we can plan for moving up in stakes, and we can give ourselves greater access to resources that we may use to enable us to take those shots at bigger games in future.

The ‘volatility paradox’

The biggest problem with using volatility as a metric that we can use to make decisions is that it ends up folding over onto itself – the more volatility we take on, the more we benefit from reducing it and gaining stability, while the less volatility we take on, the more capacity we have to absorb volatility when it does come around, because we know it won’t break us Think of it like an in-game situation – if you take on lots of volatility in a tournament and play a lot of big pots, then losing one huge pot could put you out of the event, so you’re incentivized not to do that. But if you never play any big pots because you’re trying to hard to reduce volatility, then it’s very difficult to build a big stack, which means you don’t have the capacity to absorb a hit if you do take a big, unavoidable cooler.

Understanding this paradox takes time and practice. Ultimately, all we can really do is take on volatility in situations where it doesn’t hurt us, and reject it at times where it does, but EV has to remain our main focus. Taking on a huge amount of volatility for a tiny EV gain is usually a mistake, while refusing to take on any volatility even for a very big EV gain is always a mistake. As with so many things, the resolution to the paradox lies in our ability to distinguish one situation from another, and thus we must always be attentive to situations where our willingness to take on volatility forms a big portion of our decision-making process.